Authors

B. Chilisa, T. Major,M. Ramasobana, W. Nderitu, J. Govender, S. Koloi-Keaikitse, F. Mwaijande, B. Koyabe, Gaotlhobogwe, R. Nabbumba, M. Frehiwot, M. B. Pheko, S. Molosiwa and C. Akligo

There is a call to strengthen African-led development by empowering communities, practitioners, and policymakers to design, monitor, and evaluate projects that promote community participation, ownership, and sustainability. Do you know of projects/interventions in which evaluators, project commissioners, and funders report success, yet on the ground, change is minimal? The world is changing, and there is a push not only to evaluate projects/interventions for economic benefits but also to consider social and environmental benefits. The challenge is how to go beyond the practice of using tried and tested evaluation frameworks and tools that originate from the global North to include the use of frameworks and tools emanating from the philosophies, values, histories, and experiences of the two thirds majority of the world, whose voices are not visible in the global evaluation ecosystem. How can we decolonize evaluation so that the methods are aligned with indigenous paradigms and the world views of the communities? How can we make evaluations of interventions culturally and contextually responsive to the needs and priorities of communities?

In response to the challenge, the University of Botswana, in partnership with the University of Ghana, Africa Nazarene University, the African Evaluation Association (AfrEA), Tiyimele Consultants, and Data Innovators, formed the Pan-African Indigenous Evaluation Consortium (PAIEC) to map and co-create innovative, African-rooted evaluation frameworks (AREF) and tools. The project, funded by the Mastercard Foundation and led by the University of Botswana, conducted a systematic review to identify trends, leading thinkers, implementers, and funders in African-rooted evaluation. A SenseMaker narrative survey established how evaluation practitioners, implementers, and academics perceive reality, values and ways of knowing and how they apply these perspectives in evaluation practice. A total of 101 stories were collected from 25 African countries.

Findings from the two processes guided the development of African rooted evaluation frameworks (AREF). Five frameworks were co-created at a three-day workshop attended by 48 participants, including African think tanks, local and global evaluation experts, funders and commissioners, government representatives, development partners, leading implementers of AREF, graduate students, university academics, and civil society. The frameworks were pilot-tested in Malawi, Zambia, and Uganda.

All the co-created frameworks recognise that project activities are part of a larger system, governed by an understanding of interconnectedness, interdependence and relationship-building. All projects, therefore, emphasise relationship-building, prioritising community needs, cultural sensitivity, and respect for all. Ownership of evaluation has remained with the elites, while sustainability has become a form of evaluation conducted ± 2 years post the project ends. All frameworks include a built-in sustainability design. Nevertheless, each framework addresses a specific gap in the evaluation landscape as follows:

Ngwanake Cultural Empowerment Framework (NECF): NECF strengthens youth capacity to integrate indigenous knowledge and technology into project design and monitoring and evaluation (M&E). It is a participant-driven evaluation in which youth conduct their own evaluation with the support of the evaluator.

People, Environment, Place, Space, and Time Context-Responsive Framework (PEPST): It focuses on context, exploring how a worldview that honours people’s relationships with one another and with the universe may influence project/intervention implementation and perspectives on what counts as project benefits and success. This includes building relationships, changing mindsets, integrating knowledge systems, caring for the environment, and future thinking, all of which are important to measure to advance a transformative agenda.

The Pamoja Safarini Theory of Practice (PSTP): It’s an indigenous Theory of Change that integrates African worldviews. The framework introduces six interconnected principles that guide programme design, implementation, and evaluation across the full project cycle.

The Engagement, Participation, Involvement, and Ownership (EPIO): A planning and management framework that ensures communities are meaningfully engaged at every stage of project design and implementation. It promotes community collective ownership of projects, enabling community-driven decision-making and long-term project impact. It brings a new approach to planning, managing, and evaluating projects that leads to people-centred solutions, engagement, participation, involvement, and ownership.

Community Language-Based Evaluation Framework (COLABEV): The COLABEV is a four-stage framework that enables evaluators to conduct evaluations across the initiation, design, data collection, reporting, and communication phases, using community languages.

Can you use any of these frameworks in conducting an evaluation? In this article, we present the PEPST framework and its application. Other frameworks are scheduled for presentation throughout the year 2026.

PEPST Context Responsive Framework

The PEPST Context Responsive framework is an African-rooted, people and context-centred evaluation tool that promotes a holistic approach to contextualising project/intervention planning and evaluation, moving evaluation towards systems thinking and building futures. Context is the interconnectedness and relationships among people and the environment. The value of collective responsibility and the co-creation of knowledge through interactions in a spiritual world is central to the meaning of context. Spirituality refers to the worldview that the living and the non-living, that is, the human beings and all nature, are related. The people must respect and nurture the environment. The concepts of environmental justice and environmental responsibility are drawn from this worldview.

The framework is grounded on: 1) Connectedness, Interdependence, and Harmony, 2) Preservation of the sacred, 3) Mutual respect and humility (relationality),4) Sensitivity to cultural norms and values of any group, 5) Responsibility and accountability to and by members of the society and 6) relational coexistence. The framework has five elements: People, Environment, Place, Space and Time. These are systems of relationships that cannot be separated, offering an integrated approach to evaluation that requires understanding of how projects/interventions operate within a larger system of people, the environment, and a complex social, cultural, and political context. Each element is outlined below:

People

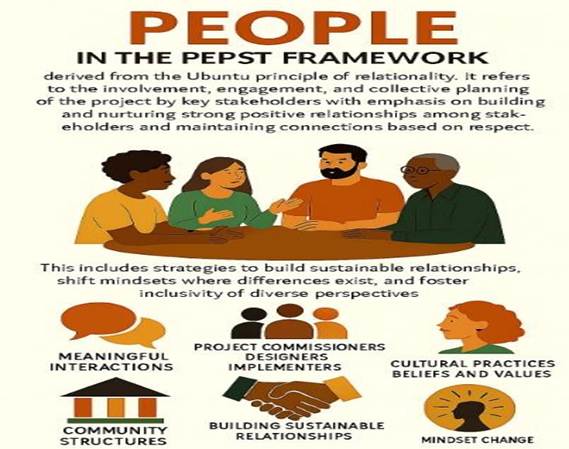

Figure 1: A depiction of the People element

There is emphasis on the importance of interactions and conversations between project commissioners, designers, implementers, relevant community structures, and intended project recipients. These initial conversations must recognise that people bring their unique cultural practices, beliefs, and values, which can significantly influence how they understand the problem the project/intervetion aims to address, how it will be implemented, and what success indicators should be used, fostering stakeholder participation. Participation measures include inclusive participation, strategies and activities to build sustainable relationships, changes in mindset where differences exist, and the inclusion of diverse perspectives. Evaluators can explore the following questions: Who designed this project? Who implemented? Who owns it? Through the joint use of cocreation and qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods participatory approaches or data tools, the following questions can guide project/intervention planning and inform judgments about community participation and expected outcomes:

- Who are the stakeholders and what are their roles and responsibilities?

- Are there strategies to facilitate communication, engagement, and relationship building among stakeholders, and how do these impact the success of the project/intervention

- Are there strategies to address the change of mindsets where stakeholders have different perspectives, and how does this impact project/intervention success

- What are the co-created project/ intervention objectives,s implementation strategies and impact evaluation indicators?

- How has stakeholder participation influenced the adaptation of the project/intervention?

Environment

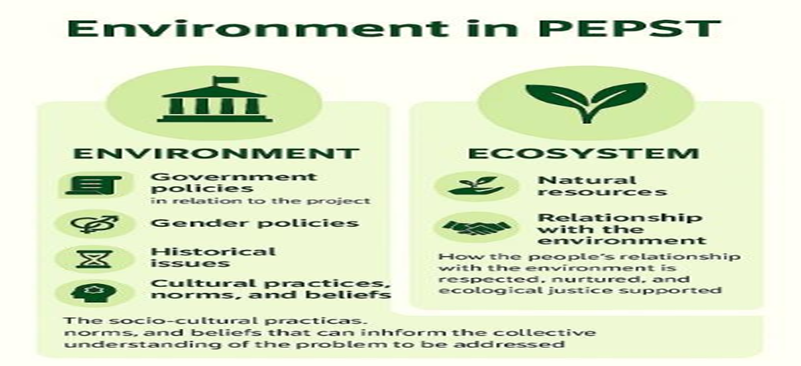

The environment refers to the conditions, such as government policies, gender policies, socio-cultural norms, and beliefs that inform collective understanding of the problem to be addressed, environmental responsibility, and the use of technology necessary for the project’s success. Environmental responsibility requires project designers and recipients to make conscious efforts to minimise environmental harm by ensuring that project activities do not damage the environment. Guided by the Ubuntu principle of respect for one another and the environment, projects and interventions should cause no harm to people or the environment. The evaluation focuses on resources and the implementation process; environmental impediments to project outcomes and impact; and project activities that might harm the environment. While this aspect of the framework can be used for project planning, it is strongly recommended for assessing project inputs and the implementation process.

Figure 2: A summary of the Environment element

Data tools can be co-created to address the following themes:

- Cultural practices that impacted the implementation, output and outcome

- Gender norms that impacted the implementation, output, and outcome

- Policies that affected implementation

- Activities that addressed mindsets to optimise project outcomes, continuity, and sustainability.

- Activities that have the potential to damage the environment or community relations

- Overall implementation success and impact on project outcomes.

Place and Space

This aspect of the tool continues the assessment of the planning and implementation process, with an emphasis on inclusivity and the integration of local indigenous science with other knowledge systems to support localised solutions, expansion, growth, and a forward-looking approach. It makes a judgment on the project/ intervetion’s adaptation to local contexts and the resulting outcomes.

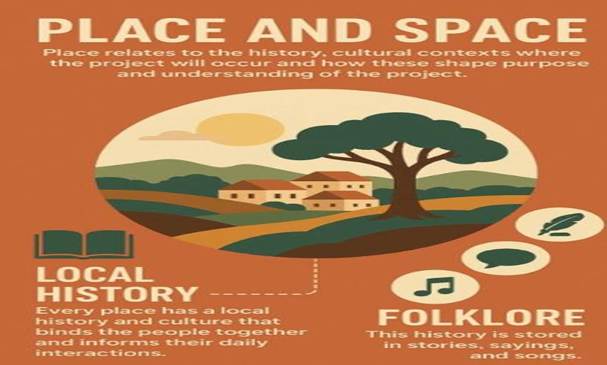

Figure 3: A depiction of the Place and Space element

Place refers to the history and cultural contexts in which the project will occur and how they shape the project’s purpose and understanding. Every place has a local history and culture that bind people together and inform their daily interactions. This history is preserved in folklore: stories, sayings, and songs. Space refers to beliefs about the physical environment of project activities, which may have a positive or negative impact on the project. People have connections to their land and space, and there may be areas where it would be against community practice to site a project.

Under Place and Space, the evaluator moves away from the practice of implementing programs as planned, to accommodate the project’s adaptation to context and community needs, and to support community participation, including identifying areas where changes in project implementation and outcomes have occurred in response to the project’s location, cultural practices, and people’s needs and priorities. The main evaluation question concerns the extent to which the project/intervention is compatible with the needs and priorities of the people, its synergy with place and space, and the design and implementation adaptations that respond to place, space, and the future. The following themes can be addressed:

- History of the place that informs the choice of projects

- Information on the place and space that can facilitate or hinder the implementation, success, and outcome of the project

- Community resources and assets that the projects/intervetion leverage on

- How the project leverages on community indigenous science, resources and assets to inform project design and implementation

- Project responsiveness to community context and needs

- Community indicators of success

- Community strategies for sustaining outcomes.

Time

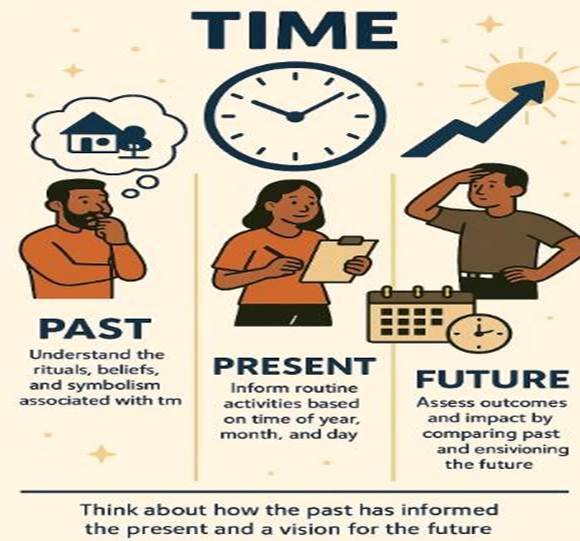

Figure 4: A summary of the Time element

Time means looking back to the past, engaging in the present, and looking forward to the future. The success of project/intervention activities is measured against observed time patterns. Time focuses on understanding the rituals, beliefs, and symbolism associated with time and project activities, and thinking about how the past has informed the present and a vision for the future. The time of year, month, and day can inform routine activities, ultimately informing project outcomes and impact, which are assessed by comparing the past with the present and envisioning the future. Aligned with relationality and connectedness, success is measured at the individual, family, community, and systems levels. Themes to be explored include:

- Compare what was at the start with what is. Here, evaluators may assess progress against the project goals and objectives co-created with the stakeholders.

- Responsiveness to the changing environment: Measure changes, improvements, and adaptations made during implementation, along with the strategies and outcomes. Specific places, communities, and cultural practices may have required adaptations to the project. Local indigenous science may have been integrated into the design for innovative implementation and project outcomes.

- Individual and family success stories using community methods

- Measure systems-level impact, for example, community agency, collaborative partnership, local participation and ownership, social cohesion, and strengthening of local capacity.

- Dreams for the future

This final aspect is well-suited to summative evaluation. It can be used for midterm reviews of projects/interventions or at the end of the project/intervention circle. It combines implementation measures across Environment, Place, and Space and assesses their impact on outcomes. It assesses the value added to the community by evaluating success at the individual, family, and community levels, environmental care, and prospects.

What do you think of this framework? Would you like to try it? Let us know in the comments section. Alternatively, please email our Project Lead, Bagele Chilisa, at chilisab@ub.ac.bw.